The Seven Major Tax Risks Brought to High Net Worth Shareholders by the Revision of the Company Law (Part One)

Editor's Note: On December 29, 2023, the Company Law underwent its sixth revision and is set to be officially implemented on July 1, 2024. Compared to the current regulations, the new Company Law mainly adjusts aspects such as corporate capital system, corporate organizational structure, distribution of rights and obligations among shareholders, and the establishment and exit mechanism of companies, while also clarifying the relevant responsibilities of shareholders. Against this backdrop, an increasing number of high net worth shareholders are choosing to proactively plan for capital reduction, transfer of equity to external parties, and company deregistration to cope with the potential legal liabilities that may arise after the new Company Law comes into effect. However, these actions entail considerable tax risks. Improper planning and insufficient attention to tax issues can easily lead to tax crises for shareholders. This article aims to analyze the tax risks that high net worth shareholders may face in behaviors such as capital reduction and deregistration, share transfer, non-monetary asset contribution, etc., under the backdrop of the new Company Law, in order to provide useful insights for investors.

I. Risk One: The New Company Law Clarifies the Deadline for Actual Payment of Subscribed Capital, Shareholder Capital Reduction, and Company Deregistration May Trigger Tax Risks

(I) Rule Changes

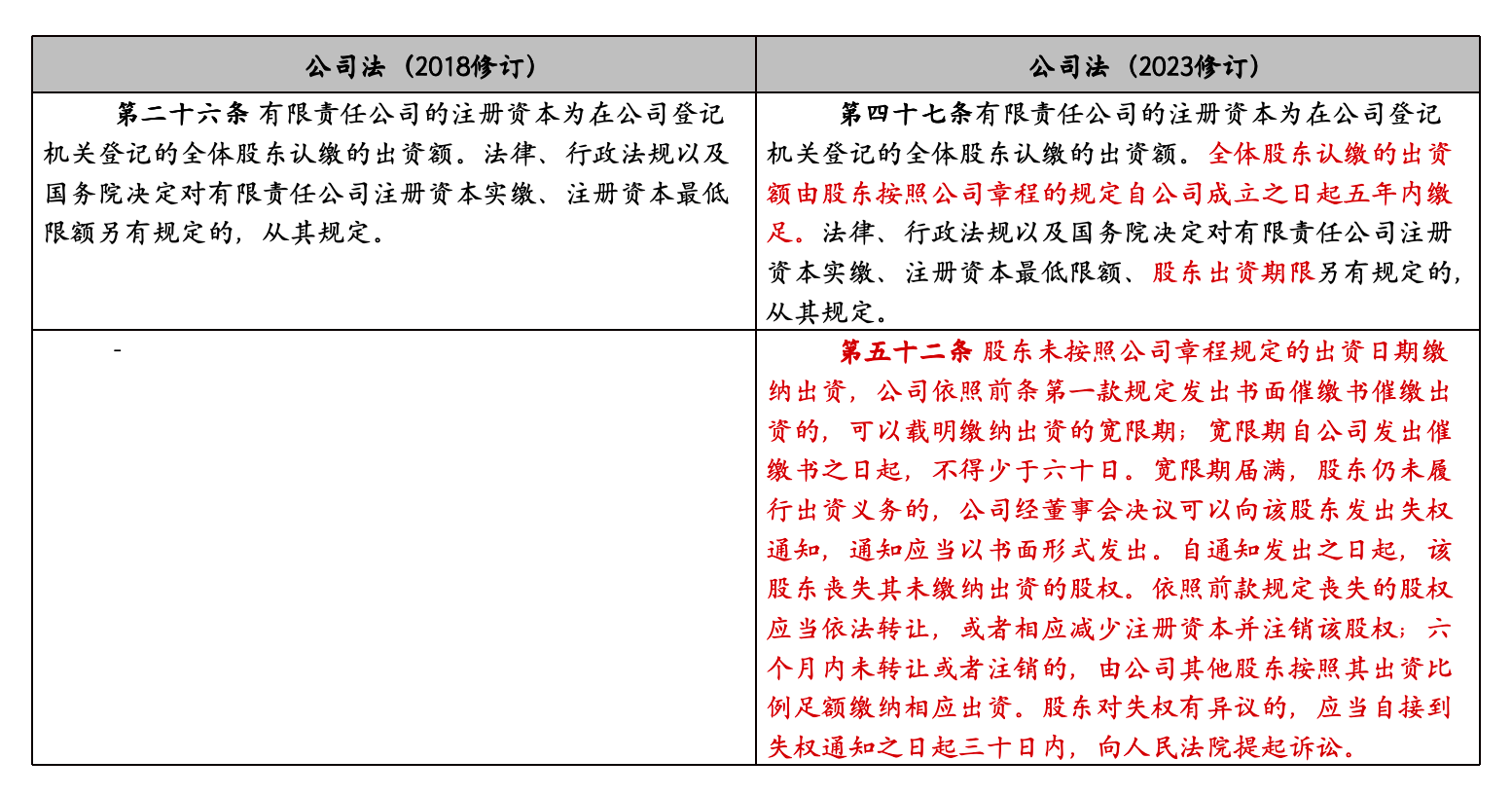

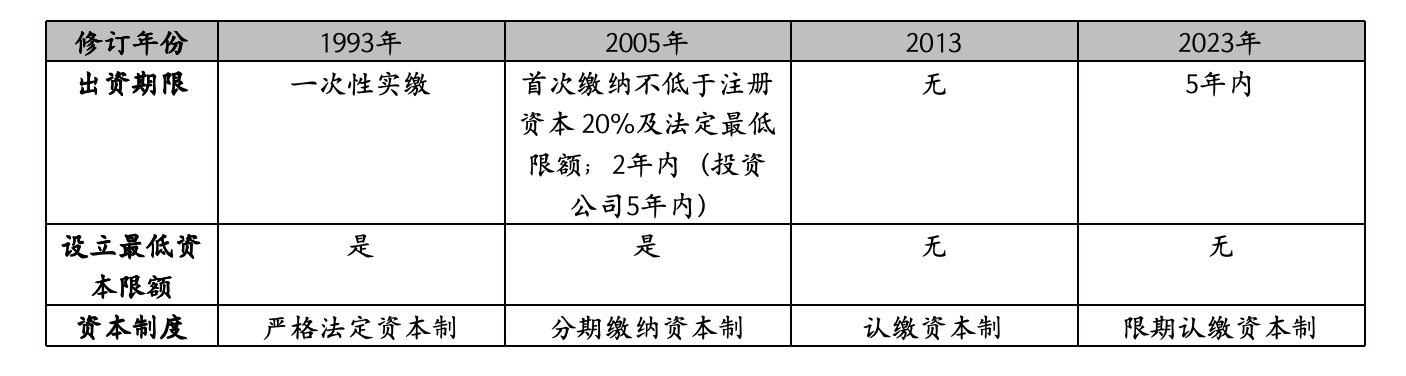

The new Company Law stipulates that the subscribed capital contribution by shareholders must be fully paid within five years, which means that companies registered after the official implementation of the revised Company Law on July 1, 2024, must pay up their registered capital within five years.

On February 6, 2024, the State Administration for Market Regulation issued the "Provisions of the State Council on the Registration and Management of Registered Capital Registration System under the Implementation of the Company Law of the People's Republic of China (Draft for Soliciting Opinions)," which sets a three-year transition period for existing companies. Similarly, the "Opinions on Fully Promoting the Pilot Registration of High-quality Development of Operating Entities (Draft for Soliciting Opinions)" issued by the Beijing Municipal Administration for Market Regulation also stipulates that unless otherwise specified by laws, administrative regulations, or State Council decisions, existing limited liability companies should adjust the remaining contribution period to within five years within three years after the new Company Law takes effect, and shareholders of existing joint-stock companies should fully subscribe for all shares within three years after the new Company Law takes effect. This sends a signal for rectification of existing companies after the implementation of the new Company Law.

(Chart showing the historical evolution of China's company capital contribution system)

(II) Deadline for Actual Payment Sparks a Wave of Shareholder "Capital Reduction," Concentrated Tax Risks May Erupt

Articles 50 to 54 of the new Company Law stipulate the corresponding responsibilities of shareholders who fail to fully pay their subscribed capital, including joint liability for establishing shareholders for the insufficient capital contribution of other establishing shareholders and the loss of corresponding rights if shareholders fail to fulfill their capital contribution obligations after being urged to do so. Therefore, to ensure the normal operation of enterprises and the reasonable transition of shareholder rights, some cash-strapped shareholders may choose to proactively reduce capital.

For individual shareholders, the tax treatment of their capital reduction generally follows the provisions of the "Announcement of the State Administration of Taxation on Issues Concerning the Levy of Individual Income Tax on the Receipt of Funds from the Termination of Investment and Business Operations by Individuals" (State Administration of Taxation Announcement [2011] No. 41, hereinafter referred to as "Announcement No. 41"). Article 1 of Announcement No. 41 stipulates: "Income received by individuals from the transfer of equity, liquidated damages, compensation, indemnities, and other proceeds obtained from the termination of investment, joint ventures, and business cooperation due to various reasons shall be subject to individual income tax in accordance with the provisions applicable to income from the transfer of property." According to the above regulations, the calculation formula for the taxable income of individual shareholders is as follows:

Taxable income = Total income received by the individual from the transfer of equity, liquidated damages, compensation, indemnities, and other proceeds obtained from the termination of investment and business operations - Original actual capital contribution (investment) amount and related taxes and fees.

Therefore, if an individual shareholder receives investment recovery funds during the capital reduction process and the amount exceeds the investment cost, individual income tax should be calculated at a 20% rate according to the "income from the transfer of property."

In addition, capital reduction can be classified into fair capital reduction and unfair capital reduction. In the case of unfair capital reduction, if some shareholders implement capital reduction while others do not, the shareholders who do not reduce their capital will incur tax risk.

First, Fair Capital Reduction

Depending on whether the payment to the reducing shareholders is based on the proportionate net asset shareholding, capital reduction can be divided into fair capital reduction and unfair capital reduction. Fair capital reduction refers to the payment of consideration to the reducing shareholders based on the net asset shareholding corresponding to their original investment. In this case, for the reducing shareholders, their taxable amount is calculated according to the aforementioned Announcement No. 41, while for the shareholders who do not reduce their capital, the capital reduction does not affect their holding of net assets, and they do not incur any tax obligations.

Second, Unfair Capital Reduction

Unfair capital reduction refers to the payment of consideration to the reducing shareholders that is not based on the net asset shareholding corresponding to their original investment and can be further divided into discounted capital reduction and premium capital reduction. Discounted capital reduction refers to the payment of consideration to the reducing shareholders that is lower than their holding of net asset shares. Premium capital reduction refers to the payment of consideration to the reducing shareholders that is higher than their holding of net asset shares. If some shareholders carry out discounted capital reduction, it will inevitably lead to an increase in the net asset shareholding of other shareholders, resulting in a benefit transfer effect for the other shareholders; if some shareholders carry out premium capital reduction, it will inevitably lead to a decrease in the net asset shareholding of other shareholders, resulting in a benefit transfer effect for the reducing shareholders. In the case of premium capital reduction, since the reducing shareholders are subject to Announcement No. 41 in calculating the taxable amount, regardless of the amount of benefit transfer, it will be included in the tax scope; however, in the case of discounted capital reduction, for shareholders other than the reducing shareholders, although they did not implement the capital reduction behavior, they passively accepted the benefit transfer, increasing the value of their holdings. Although this part of the value has not been realized, the tax authorities may still carry out tax adjustments and assess the income of shareholders who did not reduce their capital.

(III) Risk Three: Deadline for Actual Payment Promotes Shareholders to Deregister Some Companies, Liquidation Deregistration May Trigger Tax Risks

Under the capital payment deadline system, some shareholders choose to proactively deregister companies with no long-term operating business or losses. Unlike the capital reduction process, the tax issues involved in company deregistration are more complex.

Firstly, the deregistration process for companies is more cumbersome. It typically involves resolutions by shareholders for liquidation, establishment of liquidation teams, application for deregistration filing with the industry and commerce department, deregistration notice, deregistration of tax registration, deregistration of industry and commerce registration, deregistration of social security registration, closure of bank accounts, and cancellation of seals. Relevant laws and regulations have strict requirements for applying for simplified deregistration or immediate deregistration, and there is also the issue of pursuing tax liabilities from shareholders after deregistration.

Secondly, company deregistration involves multiple taxes. Not only is value-added tax payable for the assets ownership changes during the liquidation process, but corporate income tax needs to be calculated and paid based on the entire liquidation period as the tax period, and individual income tax needs to be calculated and paid for the remaining property distributed to shareholders. It is worth noting that in the liquidation process, if assets such as relevant fixed assets, intangible assets, real estate, financial assets, etc., are not realized but are ultimately distributed to shareholders in a non-trading transfer manner, despite no cash transactions, multiple tax obligations may arise. First, asset transfer falls within the scope of value-added tax, and value-added tax should be calculated and paid. Second, the liquidating company should include the assets in the liquidation income at fair value or realizable net value and calculate corporate income tax. Third, when shareholders receive the assets, they also need to confirm the income according to CaiShui [2009] No. 60 and calculate individual income tax.

Finally, the handling of assets during the liquidation and deregistration process of companies can easily trigger tax risks. For example, some shareholders may choose to abandon their claims on the company to facilitate liquidation and deregistration, but they do not correspondingly adjust the income tax of the company, which may trigger a tax audit. Moreover, during the liquidation and deregistration of companies, two tax declarations are usually required. Article 1 of the "Notice of the State Administration of Taxation on Issues Related to Enterprise Income Tax in Enterprise Liquidation" (State Tax Letter [2009] No. 684) stipulates that when a company dissolves and liquidates, it shall treat the liquidation period as a separate tax year. When an enterprise terminates operations within one tax year, there are two tax periods, the "operating period" and the "liquidation period," which are independent of each other, and the enterprise needs to settle and declare liquidation income separately.

In recent years, various regions have disclosed several cases where deregistered companies were subject to tax inspections due to unpaid taxes during their operation periods. Some tax authorities, considering that the corporate entity no longer exists, chose to go directly to shareholders to recover taxes and penalties. Taking the case of the tax bureau in City K recovering individual shareholders' corporate income tax as an example, in September 2022, the tax bureau issued a "Taxation Notice" to Company J, believing that Company J had transferred 35 million shares of unrestricted tradable shares of a listed company to its five individual shareholders through non-trading transfers, resulting in underpayment of corporate income tax, and it should make up the corporate income tax of 134 million yuan for the year 2021. Since Company J has already been deregistered, its corporate income tax should be recovered from the five individual shareholders according to their investment proportions.

In addition, tax authorities may also recover taxes through means such as forcibly restoring the tax registration of deregistered companies, believing that there was concealment of true circumstances or fraud in the deregistration process, and recover taxes and penalties from the original shareholders. If the behavior of a deregistered company is determined to constitute tax evasion, according to the "Reply of the Supreme People's Procuratorate on How to Prosecute Cases Involving Crime Units that have been Revoked, Deregistered, Had their Business License Revoked or Declared Bankruptcy" (GaoJianFaShiZi [2002] No. 4), it states: "When a unit suspected of a crime is revoked, deregistered, has its business license revoked, or declared bankrupt, according to the relevant provisions of the Criminal Law on crimes committed by units, the directly responsible persons in charge of the unit and other directly responsible persons should be prosecuted for criminal liability, and the unit should not be prosecuted." The original shareholders, actual controllers, and other directly responsible persons may also face criminal responsibility for tax evasion.

II. Risk Two: Clarification of Equity and Debt Contribution Rules Makes Tax Assessment of Non-Monetary Asset Contributions Complex, Prone to Tax Adjustments

(I) Rule Changes

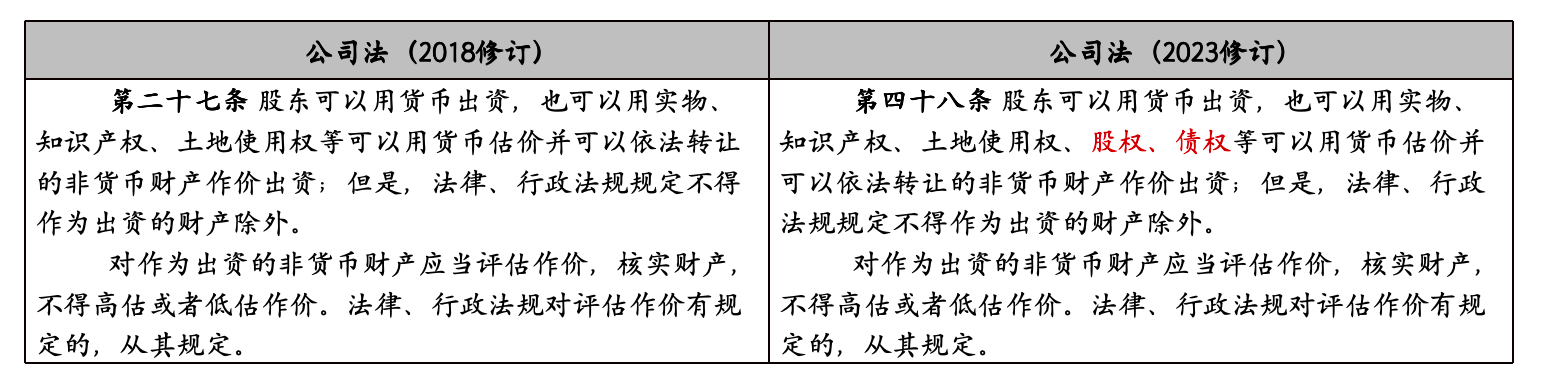

Previously, Article 11 of the "Provisions of the Supreme People's Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of the Company Law of the People's Republic of China (III)" (hereinafter referred to as "Judicial Interpretation (III) of the Company Law") and Article 13, Paragraph 3 of the "Implementing Rules for the Registration and Administration of Market Subjects" respectively stipulated the conditions for equity and debt used for capital contribution, and the new "Company Law" elevates these provisions to the legal level.

(II) Non-monetary Asset Investment Involves Multiple Tax Types, Difficult to Measure Tax Burden

With the promulgation of the new "Company Law," the deadline for actual payment system will encourage some shareholders with cash flow shortages to use non-monetary assets for capital injection, which differs from monetary contributions and involves property realization processes, thus incurring tax obligations. According to the "Notice of the Ministry of Finance and the State Administration of Taxation on Individual Income Tax Policies Related to Individuals' Investment with Non-Monetary Assets" (CaiShui [2015] No. 41), when individual shareholders invest in shares with non-monetary assets, it involves both the individual's transfer of non-monetary assets and investment. The personal income tax should be calculated and paid according to "income from property transfer." Depending on the type of contributed assets, it will also involve multiple taxes such as value-added tax, land value-added tax, deed tax, etc., making tax issues more complicated.

First, Contribution with Real Estate

According to the "Interim Regulations on Value-added Tax," taxpayers who transfer real estate for consideration shall pay value-added tax. Article 11 of the "Measures for the Implementation of Business Tax Reform Pilot Program" (CaiShui [2016] No. 36) stipulates that consideration refers to obtaining money, goods, or other economic benefits. The act of shareholders investing in shares with real estate constitutes obtaining "other economic benefits" for consideration, and value-added tax shall be levied based on the sale of real estate. Therefore, when individual shareholders contribute their own real estate to the company, it constitutes exchanging real estate for the equity of the invested enterprise, and value-added tax shall be calculated and paid at a rate of 5% based on the total price and incidental expenses minus the original purchase price of the real estate or the valuation at the time of acquisition.

The transfer of real estate by individuals may also involve land value-added tax. Announcement No. 21 of the Ministry of Finance and the State Administration of Taxation in 2021 stipulates that when individuals contribute real estate to equity investment during restructuring, land value-added tax is temporarily not levied. However, some local tax bureaus currently do not recognize non-monetary asset investment as restructuring, and require taxpayers to declare and pay land value-added tax. It is advisable for shareholders to communicate with the competent tax authorities in advance when making non-monetary asset investments. In addition, individual shareholders should provide legal, complete, and accurate vouchers, correctly calculate the amount of tax payable, and declare and pay taxes such as stamp duty.

Second, Equity Contribution as an Example

Firstly, when individuals contribute equity, according to the "Administrative Measures for Individual Income Tax on Income from Equity Transfer" (Trial) (No. 67 of 2014), the transfer of equity by natural person shareholders constitutes the transfer of equity by individuals, and individual income tax shall be paid based on the balance of the equity transfer income deducted from the original value of the equity and reasonable expenses, following the "income from property transfer."

Secondly, it is necessary to distinguish the nature of equity. If the equity contributed is shares (stocks) of listed companies, value-added tax should be paid based on financial commodity transactions, generally at a rate of 6%. If the equity contributed is of non-listed companies, it does not fall within the scope of value-added tax. According to the "Notice of the Ministry of Finance and the State Administration of Taxation on the Comprehensive Promotion of the Pilot Program for Replacing Business Tax with Value-added Tax" (CaiShui [2016] No. 36), individuals engaged in financial commodity transfer services are exempt from value-added tax. It is worth noting that behaviors that do not fall within the scope of value-added tax do not need to be declared for taxation, while those exempt from value-added tax still need to be declared.

In addition, there are differences between the definitions of non-monetary assets in accounting standards and tax policies and the new "Company Law." According to "Enterprise Accounting Standard No. 7 - Exchange of Non-Monetary Assets" and the "Notice of the Ministry of Finance and the State Administration of Taxation on Tax Policy Issues Related to Enterprise Income Tax for Enterprises Investing with Non-Monetary Assets" (CaiShui [2014] No. 116), accounts receivable or promissory notes are still considered monetary assets. However, under the new Company Law, they fall under the category of non-monetary assets. Different asset natures will lead to different tax treatment rules, so shareholders need to pay special attention when dealing with tax matters to avoid tax risks.

III. Risk Three: Although Shareholders' Capital Contributions Have Not Been Paid, Fair-Priced Transfer of Equity Still Carries Tax Risks

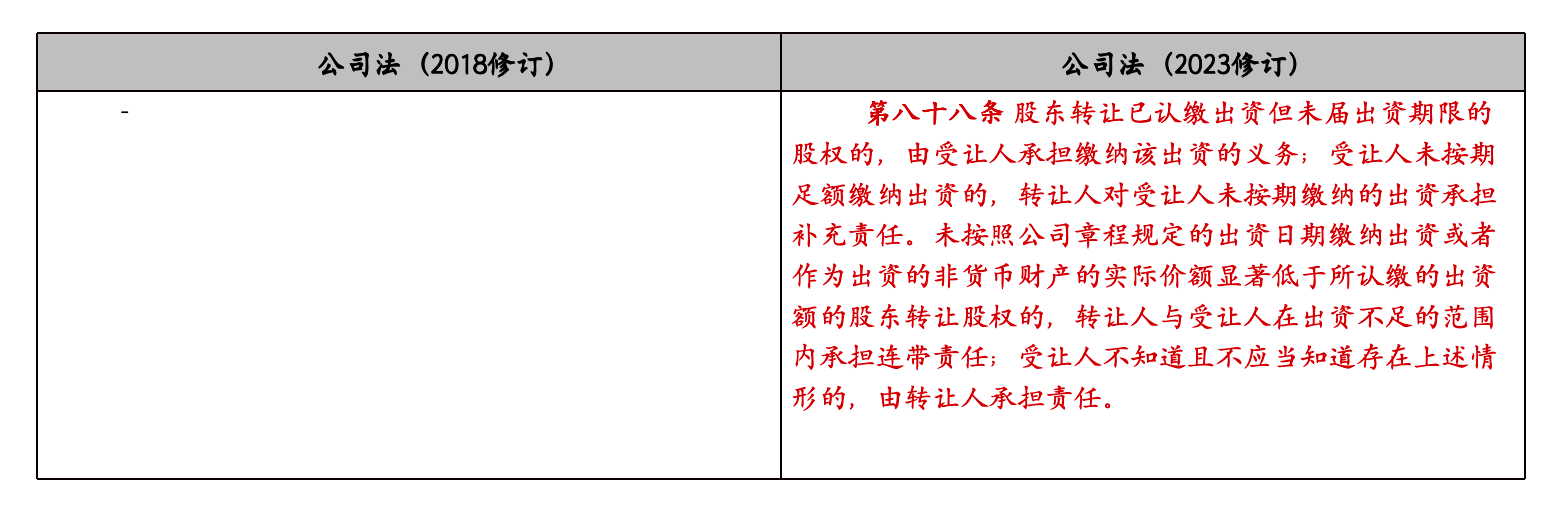

(I) Rule Comparison

As mentioned earlier, the new Company Law emphasizes capital adequacy to ensure timely recognition of subscribed capital. Article 88 of the new Company Law stipulates that original shareholders bear supplementary liability for the transfer of defective equity. If the transferee fails to pay the capital in full and on time, the transferor shall bear the supplementary liability.

(II) Although Shareholders' Capital Contributions Have Not Been Paid, Fair-Priced Transfer of Equity Still Carries Tax Risks

As the deadline for actual payment approaches with the implementation of the deadline payment system, some shareholders seek to reduce the amount of capital to be paid and avoid the supplementary liability for the transfer of defective equity by transferring equity to third parties at zero or low prices. However, according to Article 11 of Document No. 67, "Where one of the following circumstances applies, the competent tax authority may determine the income from the transfer of equity: (1) The declared income from the transfer of equity is significantly lower without justified reasons..." Transferring equity at zero or fair prices can easily attract the attention of tax authorities, who may reassess the transfer price of equity.

Some shareholders believe that since their subscribed capital has not been actually paid, the corresponding capital contribution obligation should be borne by the transferee, so they can transfer equity at a lower price. However, this viewpoint is difficult to be recognized by tax authorities. Firstly, the actual payment of capital constitutes a future debt relationship to be fulfilled. After acquiring the equity, the transferee can proceed with capital reduction, making it difficult to confirm the future actual payment of capital. Secondly, there is no legal basis for deducting the future possible actual payment of capital from the income from the transfer of equity. Lastly, the future actual payment of capital constitutes a potential consideration, and except in explicitly specified circumstances, tax laws generally do not recognize the advance deduction of potential consideration. Therefore, shareholders should assess the value of equity reasonably to reduce tax risks when transferring equity.

Some argue that if the transferee fails to fulfill the capital contribution obligation in a timely manner, supplementing the corresponding capital contribution by the transferor constitutes an increase in the original value of equity, and the transferor's income from the transfer of equity should be adjusted accordingly. However, in practice, the transferor has already fulfilled the corresponding tax obligations before the industrial and commercial registration. If the tax authority approves the subsequent adjustment of the original value of equity by the transferor's subsequent supplementation of capital contribution, it will be necessary to refund the excess tax paid by the transferor, posing significant uncertainty risks.

In subsequent articles, we will further analyze the four other major tax risks faced by high-net-worth shareholders under the background of the new Company Law. Stay tuned for more information.